The Therapy Sessions

Thursday, October 07, 2004

Tribal societies

Robert Guest, Africa editor for The Economist, speaks the truth...very un-PC, but absolutely true:

Nigeria, like much of Africa, ought to be rich but is miserably poor. The main reason is that rather than striving to create an environment in which their people can freely seek prosperity and happiness, most African governments have chosen instead to rob them. This culture of criminality has spread throughout the ruling class, down to the Nigerian border guard who threatened to beat up my driver last month if I didn't give him a dollar, to the bribe-hungry Cameroonian police officers who stopped a truck I was riding in 47 times in 300 miles.

This corruption makes it hard to do business in Africa. Manufacturers need smooth roads, reliable electricity and efficient ports. But too often in Africa, the roads are craterous because someone has looted the maintenance budget, the power fails because the state monopoly utility company is staffed with politicians' idiot cousins, and the customs officers hang onto your goods for weeks in the hope that you will bribe them to hurry up. In only two African countries - South Africa and Botswana - is it relatively easy to do business, a recent World Bank study found. For bright, energetic Africans, it is often easier to get rich by joining the government than by creating honest wealth.

That is why the debt relief proposal debated over the weekend in Washington by officials from the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the Group of 7 nations would be not be a panacea for Africa. Faster debt relief is a good idea for countries with relatively clean, pragmatic governments that pursue sensible economic policies, like Mozambique and Uganda. But debt relief cannot help the worst-governed countries like Zimbabwe and Angola because their leaders are likely to squander the money it frees up. In those places, extra cash props up despots.

This is a more complex picture than many debt-relief campaigners will admit. It may be, as Oxfam complains, that Zambia cannot hire enough teachers because the monetary fund has told its government not to run too large a budget deficit. But that is not the whole story. The main reason Zambia is bankrupt is that it has been ruled with startling incompetence and venality; for example, its previous president, Frederick Chiluba, is facing multiple charges of embezzlement.

Outsiders cannot fundamentally change the way Africa is governed. That is a task for Africans themselves, and some are rising to the challenge. In Nigeria, President Obasanjo has hired a team of technocrats to curb corruption by making the public accounts more transparent. They are doing their best, but one of them told me that probably no more than one powerful Nigerian in 20 supports the clean-up. That in a nutshell is why Africans are poor: their leaders keep them that way.

When I was a Peace Corps teacher in Sierra Leone, my principal surprised me one day with a gift: several cans of fish from Norway. My diet was low in protein and I enjoyed eating them very much.

A few days later, I saw him and thanked him. He replied that I could thank him by helping him. He wanted to get a US government grant to build a pig farm for his school, and I could help.

The principal was a wealthy man, and he probably could have afforded to finance the pig farm with his own resources. The more I heard about his little project, the more it repelled me. The pig farm, which he said would be “for the students,” would be located behind his house, out of sight, behind a wall. It would be managed by several of his twenty or so children.

But nothing raised my suspicion as much as this: I soon learned that the cans of fish I had eaten were part of a shipment that had been given to him by the World Food Program. They were intended to relieve the malnutrition of his students, and the principal was giving them away to make friends. Later, he started selling them to vendors in the market and pocketing the money.

Food that was intended to feed children was being used to make the principal into a “big man,” a wealthy power broker in Africa.

Aid in Africa is often the story of unintended consequences.

"Debt relief" - as nice and as fair as it sounds - will be no different.

I saw the beautiful side to Africa when I was there: wonderful caring people who embraced me and looked after me. There is - apparently - very little selfishness in the African character: they share willingly, and do favors for everyone, trying to make friends:

But this habit turns sinister when they get into power. A wealthy man is expected to give big gifts to his friends, and his friends - now enriched - are fiercely loyal to him. They help maintain his power.

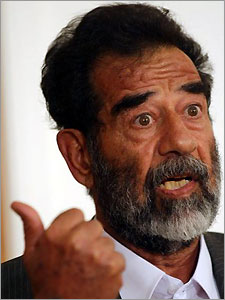

This is how tribal societies work. It explains Iraq, as well as most of Africa.

Leaders are supposed to use whatever means they can to support those who helped them along the way. Anyone who does not play by these rules will have few friends (and thus no power). The cardinal sin in West African society is to refuse to play, and to be thought stingy (or as Sierra Leonians delightfully called it: "krabbitz.")

We see it as corruption, and when leaders do it, it is.

They don't, and that is part of the problem.

It is why any government we set up in Iraq is likely to be corrupt.

It might not be cruel. It might not be a threat to the world.

But it will be corrupt.